What is Thalamic Pain Syndrome?

Thalamic Pain Syndrome occurs when damage to the thalamus disrupts normal sensory processing, causing non-painful sensations to feel painful.

Thalamic Pain Syndrome happens when a part of the brain called the thalamus is damaged. The thalamus helps control how the body feels pain. When it’s injured, often because of a stroke, a traumatic brain injury (TBI), or another cause, the brain may mix up signals from touch and other senses. As a result, something that normally wouldn’t hurt might feel painful.

This happens because the thalamus can no longer correctly interpret sensory signals, including temperature, pressure, and touch, causing the brain to misread normal sensations as painful. Thalamic Pain Syndrome is less common than other kinds of pain after a stroke, but it still affects about 8% of stroke survivors.1

It is also known as Central Post-Stroke Pain (CPSP), Central Neuropathic Pain, or Dejerine-Roussy Syndrome.

How Thalamic Pain Syndrome Develops in Stroke and TBI Survivors:

Symptoms often develop months after the initial injury as the brain heals, rewires, or becomes inflamed.

Stroke-Related Thalamus Injury

After a stroke, it’s common for a person to experience paralysis or weakness on one side of the body. As recovery begins, the affected areas, such as an arm, leg, or one side of the face, may still feel weak or numb. These symptoms usually improve over time through occupational and/or physical therapy (OT and/or PT) and the brain’s ability to heal and adapt, a process called neuroplasticity.

Delayed Onset After TBI

People who develop Thalamic Pain Syndrome typically don’t notice symptoms right away. They often begin to appear about three months after a stroke.2 The same delay is often seen in people recovering from TBIs.

Inflammation From Repeated Head Impacts

Recent studies have also found that moderate to severe concussions, as well as mild but repeated hits to the head, can cause inflammation in the thalamus.3 Over time, this inflammation may lead to the development of Thalamic Pain Syndrome.4

The three main results of Thalamic Pain Syndrome are:

- Hyperalgesia: an unusually strong sensitivity to pain, where even normal pain feels more intense than it should.

- Allodynia: pain that occurs from something that normally wouldn’t hurt, such as the light touch of a feather on the skin.

- Incorrect temperature sensations: when the brain misreads temperature signals, causing mild warmth to feel like burning or pain when the temperature changes.

Who is at Risk for Thalamic Pain Syndrome?

People with neurological injuries, including stroke, TBI, spinal cord injuries, or certain diseases, are at higher risk.

Additional neurological or systemic conditions can increase the risk of developing Thalamic Pain Syndrome, including:5

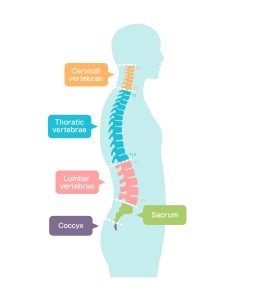

- Spinal cord injuries at or above the T6 vertebra

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Later stages of Parkinson’s disease

- Brain tumors

- Severe epilepsy

- High exposure to toxic chemicals, such as mercury

Spinal Cord Injury Survivors and Thalamic Pain Syndrome:

The spine is made up of 33 small bones called vertebrae, which are divided into five regions. When an injury occurs in the lower or middle spine, but below the thoracic T-6 vertebra, it can cause partial paralysis, often affecting only the legs. This condition is known as hemiplegia.

An injury at or above the T-6 vertebra, however, is usually much more serious. It can lead to paraplegia, a condition that causes paralysis in all four limbs.

Among spinal cord injury survivors, Thalamic Pain Syndrome is ranked as the third most life-impacting complication.6

Causes and Symptoms of Thalamic Pain Syndrome

Damage to the thalamus disrupts communication with the cortex, leading to misinterpreted sensations and chronic pain.

The Relationship of the Brain’s Thalamus plus Cortex to Pain:

The thalamus sits within the brain. It connects and communicates with the cortex, the area of the brain that sends signals to the spinal cord, which then passes those messages to the nerves, muscles, and tissues throughout the body.

The brain’s cortex is also responsible for higher-level functions, such as:

- Memory

- Problem-solving and decision-making

- Mood regulation, including feelings of depression or anxiety

- Interpretation of sensations within or on the body, such as pain

Without a properly working thalamus to pass these signals along, the brain would be unable to feel or recognize any sensations.

Thalamus Injury and Symptoms:

When the thalamus or its nerve pathways are damaged, a wide range of symptoms can appear. These may include both a misinterpretation of normal sensations as pain and an inability to feel certain sensations, such as pressure.

In many cases, sensations related to touch become confused, causing even light contact on the skin to feel painful. People with Thalamic Pain Syndrome often describe these feelings as burning or pin-pricking sensations.

Because of how the thalamus connects and communicates with the cortex and other parts of the brain, strokes that affect the right side of the brain are more likely to lead to Thalamic Pain Syndrome.⁷

How a Stroke Causes a Thalamus Injury:

In stroke survivors, injury to the thalamus is usually caused by either bleeding within the thalamus or a blood clot in the brain that disrupts normal blood flow to this area. When this happens, brain and nerve cells in the thalamus can die, leading to errors in how sensory messages are sent to other parts of the brain.

As a result, the symptoms of Thalamic Pain Syndrome develop when the damaged thalamus can no longer properly relay sensory information, such as heat, cold, or changes in temperature, to the cortex.

How Thalamic Pain Syndrome Affects Daily Life

Chronic pain and mood changes can significantly affect functional independence, emotional well-being, and motivation.

People with Thalamic Pain Syndrome or other forms of chronic pain are more likely to experience chronic depression. About 70% of stroke survivors with a thalamus injury develop ongoing depression.⁸ This depression can be biologically linked to changes in brain regions involved in mood regulation, and it can also develop in response to chronic neuropathic pain.

At the same time, chronic pain, no matter its cause, can also lead to depression over time. This pain-related depression can then result in:

- Less interest and satisfaction in social activities, often leading to increased isolation

- Reduced motivation to take part in physical activity

- Sleep problems, including insomnia

- More frequent suicidal thoughts and a higher risk of suicide attempts

- Lower participation in physical or occupational therapy, especially among people recovering from stroke, TBI, or spinal cord injuries

Living with Thalamic Pain Syndrome can make it harder to regain lost motor skills, largely because of the ongoing chronic pain and depression that often accompany the condition. For many stroke and TBI survivors, the same injury that caused the brain damage can also affect thinking abilities, including short-term memory and decision-making.

These combined challenges can lead to a significant loss of personal independence, making it difficult to perform everyday tasks without help.

Thalamic Pain Syndrome and Chronic Neuropathic Pain

Thalamic Pain Syndrome is one form of chronic neuropathic pain, which can originate from injuries to the central or peripheral nervous system.

CNS vs. PNS Neuropathic Pain

Thalamic Pain Syndrome (also called Central Neuropathic Pain) is a form of Chronic Neuropathic Pain. The term Chronic Neuropathic Pain refers to all pain that originates in the Central Nervous System (CNS). The two types of pain included in Chronic Neuropathic Pain are:

- Thalamic Pain Syndrome

- Chronic Peripheral Nerve Pain (the system of nerves that extend from the spinal cord throughout the body)

Although both conditions involve the CNS misinterpreting sensory information, Chronic Peripheral Nerve Pain (CPNP) has a different cause. It results from damage to the nerves that connect to the spinal cord, rather than injury to the thalamus itself.

Even without direct damage to the thalamus, the nerve pathway disruptions between the spinal cord and brain prevent the thalamus from correctly processing sensory information, leading to ongoing pain and sensory confusion.

Understanding the different types of chronic nerve pain is essential, because treatment depends on the underlying cause.

The Emotional and Psychological Impact of Chronic Neuropathic Pain:

Chronic Neuropathic Pain can make it difficult for a person to focus on anything other than the pain. It often leads to feelings of frustration and depression, and can even increase the risk of suicidal thoughts. Studies show that up to 50% of people with chronic pain experience suicidal thoughts, and nearly 9% of all suicides are linked to chronic pain.9

Any form of Chronic Neuropathic Pain can worsen both depression and anxiety. In turn, these mental health conditions can make pain feel even more intense. This happens because the brain chemicals released during periods of depression or anxiety can heighten the body’s sensitivity to pain. For people living with Chronic Neuropathic Pain, these challenges can create a vicious cycle where pain increases depression and anxiety, and those emotional struggles, in turn, intensify the pain.

Mental health problems can also lead to declines in cognitive functioning, including trouble focusing, weaker short-term memory, and reduced problem-solving skills. Because of this connection, stroke, TBI, and spinal cord injury survivors especially benefit from ongoing mental health therapy. Consistent emotional and psychological support can improve recovery outcomes, including better management of chronic pain.

Diagnostic Tools Used to Diagnose Thalamic Pain Syndrome

Diagnosis includes brain imaging and neurological exams to distinguish neuropathic pain from other conditions.

Brain Imaging (MRI and CT Scans)

The main way doctors diagnose Thalamic Pain Syndrome is with a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan of the brain. Doctors usually order this scan for someone who had a stroke or a TBI and is reporting symptoms that might point to Thalamic Pain Syndrome.

In stroke or TBI survivors, an injury to the ventrocaudal areas of the thalamus is strongly linked to a higher risk of Thalamic Pain Syndrome.10 Because of this, MRIs and other brain scans are important for helping doctors correctly understand a patient’s symptoms and identify them as Thalamic Pain Syndrome rather than something else.

Neurological Exams and Pain Assessments

Diagnosing Thalamic Pain Syndrome requires both a physical exam and a neurological exam, in addition to brain scans. These evaluations help doctors tell whether a person’s symptoms come from Thalamic Pain Syndrome or another form of chronic pain. Two common survey tests are:11

- Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS)

- Neuropathic Pain Diagnostic Questionnaire (DN4)

Managing Thalamic Pain Syndrome

Treatment typically combines medical and non-medical strategies to reduce pain and improve daily function.

Thalamic Pain Syndrome is treated with both medical and non-medical methods. However, the chances of fully stopping the chronic pain are low.12 Because of this, most people need long-term, ongoing management. This usually means using a combination of treatments instead of relying on just one approach.

Medical Pain Management Strategies:

The following medical treatments are commonly used to help reduce the pain experienced by people with Thalamic Pain Syndrome:

- Drug therapy, which may involve antidepressants, anticonvulsants, opioids, or certain IV medications

- Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation (TES) and other types of electrical stimulation.

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HOT)

- A last-resort brain surgery called Stereotactic Thalamotomy, which is done to stop the person from feeling pain at all

Non-Medical Pain Management Strategies:

There are many non-medical approaches to help manage pain. In addition to OT and/or PT, these non-medical strategies include:

- Exercise and movement: Daily aerobic exercise can help shift attention away from pain and boost chemicals that improve mood. Gentle, relaxing movement also helps keep muscles and joints working well.

- Psychological and emotional support: Mental health therapy is often needed because depression and anxiety can make self-care and social activities harder. Support from family, friends, and care partners helps keep the person connected and focused on enjoyable activities.

- Manual therapy and mobilization: Manual techniques can calm nerve pain and reduce tightness in joints and tissues. Therapists may start away from the painful area and use gentle touch to build trust and reset movement patterns.

- Desensitization techniques: Therapists slowly help patients get used to touch by starting with very gentle sensations. This step-by-step approach is important because many people with Thalamic Pain Syndrome cannot tolerate touch at first.

- Play around with modalities that offer hot or cold. Therapists and patients work together to decide whether heat or cold feels more soothing. They should avoid forcing a choice or using temperatures that are too extreme.

- Compression: Gentle, even compression can help patients feel more comfortable and protected. Gloves, stockinettes, or other products can be used during activities or flare-ups to provide steady pressure and relief.

- Mirror therapy. The patient hides the painful limb and watches the reflection of the non-painful limb while moving it. This “tricks” the brain into thinking the painful limb is moving without pain, which can retrain pain pathways.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy. CBT helps patients understand their real situation and avoid harmful or unhelpful thoughts. It teaches them skills and choices that can improve how they manage chronic pain.

We use the term “care partner” to be more inclusive of all types of people who support their loved ones with long-term health conditions, and because it matches our mission of empowering the individual to be in control and in charge of their own health and condition. It also implies that the individual is partnering with their loved one rather than “giving” their loved one a service.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

People with Thalamic Pain Syndrome often lose some independence and experience more depression and anxiety, which lowers their overall quality of life. Because of this, family members, friends, and care partners should encourage the person, especially someone recovering from a stroke or TBI, to focus on what they can do, such as feeding or dressing

Social activities can improve thinking skills and mood, so staying socially connected can support ongoing recovery and quality of life. Even with painful sensations, many people with Thalamic Pain Syndrome can still stay independent, and emotional support helps them stay motivated to work towards their goals.

Caregivers and loved ones can support someone with Thalamic Pain Syndrome by:

- Not suggesting they are exaggerating their pain.

- Affirming their experience while also encouraging self-care tasks that maintain independence.

- Continuing to spend time with them socially, even when their chronic pain feels frustrating.

With consistent encouragement and support, a person with Thalamic Pain Syndrome is more likely to improve or maintain independence, which can help reduce depression and anxiety. This often leads to a better sense of well-being and an overall higher quality of life.

©2025 Kandu, Inc. All Rights Reserved. | 8090.954.E

References:

- Tamasauskas A, Silva-Passadouro B, Fallon N, et al. (2024). Management of Central Poststroke Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain 104666. Webpage: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1526590024006229

- Stroke Association. Pain after stroke. Webpage: https://www.stroke.org.uk/stroke/effects/physical/pain-after-stroke#Central-post-stroke-pain-(CPSP)

- Grossman EJ, and Inglese M. (2016). The Role of Thalamic Damage in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neurotrauma 33(2): 163-167. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4722574/

- Rychlik N, Hundehege P, and Budde T. (2023). Influence of inflammatory processes on thalamocortical activity. Biological Chemistry 404(4): 303-310. Webpage: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/hsz-2022-0215/html?lang=en

- Northwestern Medicine [affiliated with Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL]. What is Central Pain Syndrome? Webpage: https://www.nm.org/conditions-and-care-areas/neurosciences/central-pain-syndrome

- Watson JC, and Sandroni P. (2016). Central Neuropathic Pain Syndromes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 91(3): 372-385. Webpage: https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(16)00073-2/fulltext

- Ri S. (2022). The Management of Poststroke Thalamic Pain: Update in Clinical Practice. Diagnostics (Basel) 12(6): 1439. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9222201/

- Scharf AC, Gronewold J, Eilers A, et al. (2023). Depression and anxiety in acute ischemic stroke involving the anterior but not paramedian or inferolateral thalamus. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1218526. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10493383/

- Themelis K. et al. (2023). Mental Defeat and Suicidality in Chronic Pain: A Prospective Analysis. The Journal of Pain 24(11): 2079-2092. Webpage: https://www.jpain.org/article/S1526-5900(23)00452-2/fulltext

- Vartiainen N, Perchet C, Magnin M, et al. (2016). Thalamic pain: Anatomical and physiological indices of prediction. Brain 139(3): 708-722. Webpage: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/139/3/708/2468765

- Arnstein P. (2016). Assessment of Nociceptive versus Neuropathic Pain in Older Adults. Specialty Practice Series Issue 1. Webpage: https://hign.org/consultgeri/try-this-series/assessment-nociceptive-versus-neuropathic-pain-older-adults

- Ri S. (2022). The Management of Poststroke Thalamic Pain: Update in Clinical Practice. Diagnostics (Basel) 12(6): 1439. Webpage: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9222201/